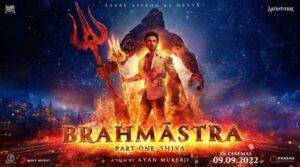

Ayan Mukerji’s Brahmastra was released on September 9. (Photo: PR Handout)

Ayan Mukerji’s Brahmastra was released on September 9. (Photo: PR Handout)

Karan Johar’s Dharma Productions has found a way to appease the market and Hindutva’s fantasy of policing Bollywood.

Written by Aakshi Magazine

Updated: September 18, 2022 8:19:48 pm

When the song ‘Kesariya’ was first released online, the internet scoffed at its use of the phrase “love storiyan”. In the way of most social media debates, it took itself more seriously than it probably should have and exhausted itself. In the week after Brahmastra’s release and box-office popularity (it’s supposed to have made Rs 300 crore in seven days), it turns out there is more to despair about than the use of a Hinglish word.

There is no other way to say it -— the excessive Hindu imagery of the song assaults your senses. Here is a couple professing love to each other, something that the long-standing tradition of the Hindi film song has celebrated in varied public spaces like parks, monuments or the middle of busy market places. The song, set in Varanasi, adds a temple and extreme ritualism to this list. There is an extended sequence of the couple sitting in front of a shivling, hands folded, taking part in the ritual before gazing at each other lovingly and approvingly — the ideal Hindu couple. (In real life, ironically, the couple might have to try harder — they were refused entry into an Ujjain temple over Ranbir Kapoor’s alleged comments about eating beef).

The implications of the choice of setting have never been innocent. In her book on love and romance in Bombay cinema of the 1950s, Aarti Wani described cinema’s use of public spaces in this manner as the privatisation of public space. Since public spaces may not always be available for private use in real life, she argued, this was a “fantasy of the ‘occupation’ of the public sphere for ‘non-public’, personal ends”.

possibility to be transgressive — unlike real life, you could love who you wanted to and where you wanted to (within caste-prohibited limits of course). In the imagination of the love song, the couple found a space to express desire in complex, and because of the song, poetic ways. And because the language was Hindustani, the Hindi film is said to have played a role in preserving the language in song and dialogue.

Now love in the “astraverse” has become hyper-Hinduised and “kesariya”. Not just in the song, Shiva and Isha’s entire love story is embedded in a deeply religious and more specifically Hindu universe. Their first meeting is during Dussehra festivities, and the courtship (in a pandal) is sealed when Isha tells Shiva that her name means Parvati. This is the film’s equivalent of lovers discovering commonalities, discovering they are fated — how can she not support him, she says. The dialogue is not just banal, it is in fact dangerous in how it makes this excessive religiosity seem neutral. And even modern. The “boycott gang” had nothing to worry about.

The resolution might still uphold love as the solution to all ills, but there is enough damage along the way to dent the original utopian promise. Sanskritised Hindi seems to come naturally to its characters and everyone is inevitably clued in on these references — there is not even the pretence of a token religious “other” (except the appearance of a kid named Tenzing). Another song sequence where Shiva discovers his relationship to fire has the refrain — “Om deva deva…”. The tune is catchy, no doubt, but in the context of the times we are living in, where public spaces are sought to be sanitised of any non-Hindu symbols, what are we really humming?

In interviews, director Ayan Mukherji, who made Wake Up Sid and Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani before this, says that this is the first time he has used his “faith” (religion) in his work. The statement is as telling as the “modern mythology” marketing line of the film. In the very Hindu universe of Brahmastra, it seems like the Hinduisation of Bollywood is complete. The apparent distinction between hyper-bhakts like Akshay Kumar vs the rest of Bollywood can possibly end. Karan Johar’s Dharma Productions has found a way to appease the market — borrowing from both the Marvel as well as Rajamouli template of cinema — and Hindutva’s fantasy of policing Bollywood. The misled boycott calls may propel some to vouch for this film, but that seems like a trap. I may be sounding alarmist but if this film’s popularity is going to set the tone for future Hindi films, then even long-term followers are better off switching off. Aur bhi ghum hai zamane main (There are other sorrows in the world).

Aakshi Magazine, a writer based in Delhi, teaches film studies at Ashoka University and has recently co-edited ReFocus:The Films of Zoya Akhtar

© The Indian Express (P) Ltd